Paul Nash, peintre officiel britannique de la Grande Guerre

Mots-clés:

Paul Nash, Route de Menin, Printemps dans les tranchées, We Are Making a New World, Passchendaele, Vimy, Oppy wood, Ypres Salient in night, Angleterre, Belgique,

Lire les articles :

Croquis de Arno Heerings

Peintures canadiennes et britanniques de la Grande Guerre

Biographie

Paul Nash (1889-1946) est un peintre et graveur sur bois britannique. Il fréquente la Slade School of Art de Londres. Dès 1914, il jouit d’une certaine reconnaissance. Pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, il est recruté en tant qu’artiste de guerre. En 1917, il est enrôlé dans les Artits’ Rifles et part sur le front occidental.

Il travailla en tant qu'artiste officiel des deux guerres mondiales et s'attacha à peindre l'horreur des tranchées et les patrouilles des avions de chasses.

I am no longer an artist,

I am a messenger to those who want the war to go on for ever…

and may it burn their lousy souls.

Paul Nash fut d’abord le peintre anglais le plus « iconique » des horreurs de la première guerre mondiale. Il avait rejoint les troupes anglaises dans l’enfer d’Ypres, ses poumons furent atteints par une attaque au gaz à Passchendaele. Il en a fait de grands tableaux saisissants, symbolistes et réalistes à la fois. A commencer par la « Route de Menin », tableau de trois mètres de long, avec un paysage désolé, complètement détruit, avec les arbres calcinés, les trous de bombes remplis d’eau, les tranchées inondées, sous un ciel d’orage et des rayons de lumière comme des tirs d’armes à feu. Un tableau « romantique » dans lequel on voit deux petits soldats perdus marchant sur une route qui n’existe plus. Il y mélange le mystère et la souffrance, avec une grande beauté.

En 1917, il peint aussi le « Printemps dans les tranchées », avec deux soldats assoupis et, à l’arrière, un paysage déchiqueté, aux couleurs pastel. Et en 1918, il peint une lumière, la nuit, sur la tranchée d’Ypres. Il y a là le réalisme teinté du mystère d’un De Chirico ou d’un Odilon Redon. Dans « We Are Making a New World », il peint un lever de soleil prometteur sur un paysage de mort

Au front en novembre 1917 comme observateur en uniforme. Soumis à des tirs de mortier constants et découragé cette fois-ci par la destruction de la nature, Nash éprouve colère et désillusion, sentiments qui alimentent sa créativité; en six semaines, il produit cinquante dessins à partir desquels il réalise des tableaux et des estampes à son retour en Angleterre.

Les œuvres sont très stylisées, et elles expriment les horreurs de la guerre à travers des paysages qui ressemblent à un enchevêtrement d’os brisés, surplombés par un soleil froid et hésitant.

Ses œuvres

Menin Road, 1919

Nash received the commission for this work, which was orginally to have been called 'A Flanders Battlefield', from the Ministry of Information in April 1918. It was to feature in a Hall of Remembrance devoted to ‘fighting subjects, home subjects and the war at sea and in the air’. The centre of the scheme was to be a coherent series of paintings based on the dimensions of Uccello’s ‘Battle of San Romano’ in the National Gallery (72 x 125 inches), this size being considered suitable for a commemorative battle painting. While the commissions included some of the most avant-garde British artists of the time, the British War Memorials Committee advisors saw the scheme as firmly within the tradition of European art commissioning, looking to models from the Renaissance.

It was intended that both the art and the setting would celebrate national ideals of heroism and sacrifice. However, the Hall of Remembrance was never built and the work was given to the Imperial War Museum. Nash worked on the painting from June 1918 to February 1919. Nash suggested the following inscription for the painting. 'The picture shows a tract of country near Gheluvelt village in the sinister district of 'Tower Hamlets', perhaps the most dreaded and disastrous locality of any area in any of the theatres of War.'

Over the Top, 30 décembre 1917

A landscape in the snow. On the left, a red earth trench lined with duckboards stretches away from the viewer. A group of soldiers clamber from the trench, going 'over the top'. Two lie dead in the trench and another has fallen lying face down in the snow. Those who have survived plod forward towards the right without looking back. They walk beneath a grey, stormy sky, with clouds from shell and gunfire in the distance.

Field of Passchendaele, 1917

A battle scarred Western Front landscape near Passchendaele in Flanders. A large water-filled shell hole dominates the foreground, with two dead soldiers lying nearby on the left. Beyond them is the entrance to a dugout, a small bomb damaged brick structure and numerous bare tree stumps representing the remnants of a small wood. These stumps are echoed in a web of barbed wire on the right, held up by wooden stakes. On the horizon a few beams of sunlight pierce the heavy black cloud, two shells exploding to the right.

Void (Néant), 1918

Void peut passer pour l'archétype des paysages de la Grande Guerre : pas un soldat visible, un camion et des canons abandonnés, des tranchées inondées, un cadavre flasque parmi les obus et les fusils, des fumées et un avion au loin, dont on ne sait s'il bombarde ou tombe. De plus, il pleut sans cesse. Il ne reste aucun espoir de revenir intact d'un tel lieu, qui n'a plus de nom, qui n'est plus qu'un champ de mort.

The mule track 1918

Wire, 1918

Executed while Nash was commissioned as an official war artist, this drawing was originally titled Wire – the Hindenburg Line and was intended as a preparatory work for a lithograph. As with many of Nash’s work of the time, man-made fortifications and the destruction of nature act as metaphors for the horror of war.

The foreground tree stump appears to erupt from the water-logged earth in a seemingly futile bid to rid itself of choking barbed wire, and so encapsulates the bitter struggle of the Western Front. Meanwhile, a grey cloud or pall of smoke emerges in the distance and drifts ominously over the battlefield.

Oppy wood, 1917

The lower half of the composition has a view inside a trench with duckboard paths leading to a dug-out. Two infantrymen stand to the left of the dug-out entrance, one of them on the firestep looking over the parapet into No Man's Land. There is a wood of shattered trees littered with corrugated iron and planks at ground level to the right of the composition. The sky stretches above in varying shades of blue with a spectacular cloud formation framing a clear space towards the top of the composition.

A Howitzer Firing, 1917

A scene with four British artillerymen firing a Howitzer gun. They stand beneath a canopy of camoflage netting. To the right a blast of light erupts from the muzzle of the gun, and the men on the left shield their faces from the brightness.

Spring in trenches Ridge Wood, 1917

Three British soldiers waiting in a trench. One stands leaning against the wall of the trench, another sits on a step resting one arm behind his head. The third stands up looking out over the broken landscape beyond. There are the remains of a grove of trees, some of which are beginning to show new buds, and rolling hills in the distance.

A French Highway

British troops march across the foreground. They walk in rows of three, every man wearing full kit. Behind them are two mounted French officers, in their distinctive helmets and dark blue cloaks. They march along a road lined with bare, branchless trees. There is the edge of a ruined building in the left background.

An advance post, 1918

Three British soldiers shelter under a corrugated iron roof in an advanced post. Another soldier sits in the immediate foreground on sentry duty, looking towards one of the stacked rifles on the left, which has a small mirror mounted on the bayonet to enable him to view over the parapet. Beyond the shelter, the bomb-damaged hills of No Man's Land are visible, with lines of stakes designed to hold barbed wire stuck in the ground.

All four soldiers have a small blue square of cloth on their left shoulders, identifying them as men of the 63rd Royal Naval Division.

We Are Making a New World , 1918

The title mocks the ambitions of the war, as the sun rises on a scene of the total desolation. The landscape has become un-navigable, unrecognisable and utterly barren. The mounds of earth act almost as gravestones amongst the death and desolation. Nash was looking for a new kind of symbolism divorced from the more traditional Symbolist principles.

He realised that the ideas he had been presenting in a figurative way before the war could be more meaningful in pure landscape form.

The Ypres Salient in night, 1918

Painted in 1918 in his capacity as an official war artist, this work depicts a landscape well-known to Nash during his active service in the Ypres Salient with the Hampshire Regiment in 1916 and 1917.

The anonymous figures of the sentries on the fire step keep their heads down in the dazzling light supplied by the star shells bursting in the dark night sky. A peculiar feature of the Salient was the disorientation, caused by the changes in direction of the line, experienced by the defenders; this was often exacerbated at night by the almost constant discharge of shells, signal rockets and observation flares by both sides.

After the battle, 1918

A view of a Western Front battlefield in the aftermath of battle, with rain falling from the sky. Four corpses lie amongst shattered trenches, with broken duckboards, barbed wire and corrugated iron littering the scene. There are also water filled shell holes and the remains of a few bare trees on the horizon.

Sunrise, Inverness Copse, 1918

Inverness Copse was a bitterly contested area of the Battle of Paschendaele in 1917. Nash captures the savage destruction wrought upon the landscape by picturing the shattered stumps of the former copse transformed into a vast cemetery of natural forms. The weak sunlight of the new dawn that illuminates the scene offers some hope of future redemption, but this is refuted by Nash’s own feelings that on the Western Front “sunset and sunrise are blasphemies, they are mockeries to man.

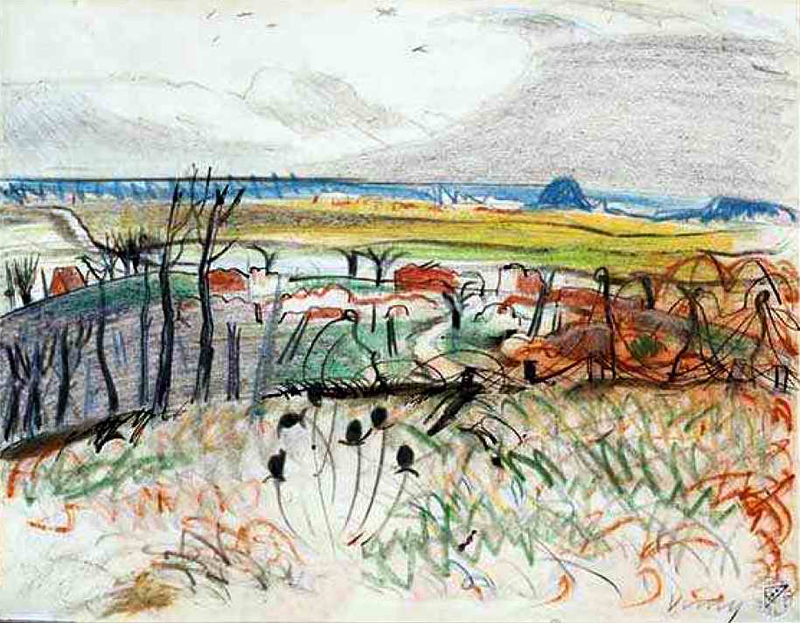

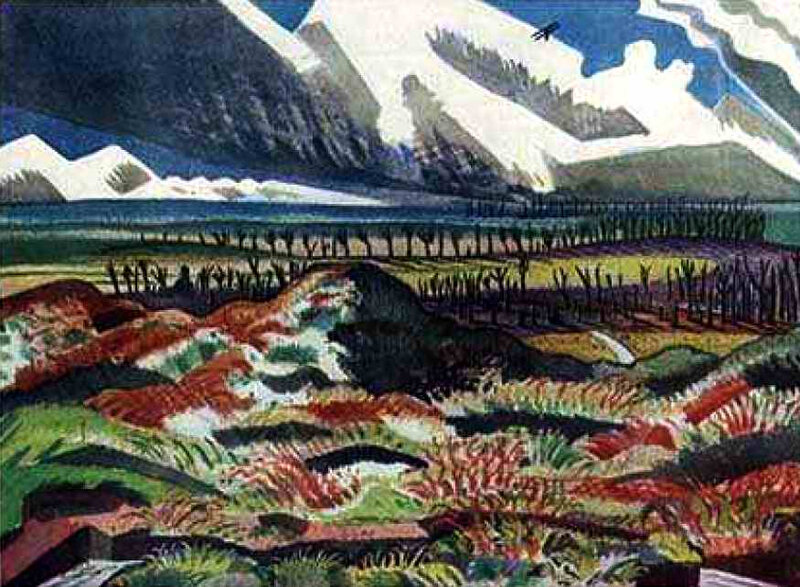

Vimy, 1917. Crayon de couleur, encre sur papier.

Ruined Country Vimy. Paysage dévasté près du bois de la folie, 1918

A landscape looking over an old battlefield near Vimy in France. In the foreground the earth is carpeted with different coloured mosses and grass, heavily scarred from past shellfire. There are lines of skeletal-like trees beyond, and dramatic clouds in the sky above. There is the small shape of a bi-plane flying through the clouds near the top of the composition.

Voir les liens :

https://www.iwm.org.uk/search/global?query=Paul+Nash

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/20064

Voir l'article :

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F54%2F22%2F1046708%2F84942430_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F87%2F07%2F1046708%2F84848064_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F87%2F08%2F1046708%2F82968948_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F32%2F93%2F1046708%2F82830637_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F90%2F33%2F1046708%2F81645279_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F13%2F30%2F1046708%2F81130434_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F47%2F54%2F1046708%2F80689925_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F55%2F77%2F1046708%2F80375841_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F72%2F64%2F1046708%2F80386697_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F02%2F48%2F1046708%2F133781363_o.jpg)

/image%2F1145881%2F20240428%2Fob_ac4ec1_capture-d-ecran-2024-04-25-070130.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F64%2F63%2F1046708%2F124954684_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F80%2F49%2F1046708%2F129280663_o.jpg)